Emile Zola’s The Belly of Paris: Celebration of Food or Satire?

Les Halles in Paris—do you know it? Unless you’re into a bit of French history, you may not. It doesn’t exist anymore, demolished in 1969/70, its centennial year. It was a huge market, much of it housed in at least ten pavilions of glass and iron designed by Victor Baltard. Plus a big domed central pavilion that later became the Bourse de Commerce, the French stock exchange. Everything you could imagine to be edible could be found there, from fish, meats, and cheeses to fruits, vegetables, and herbs.

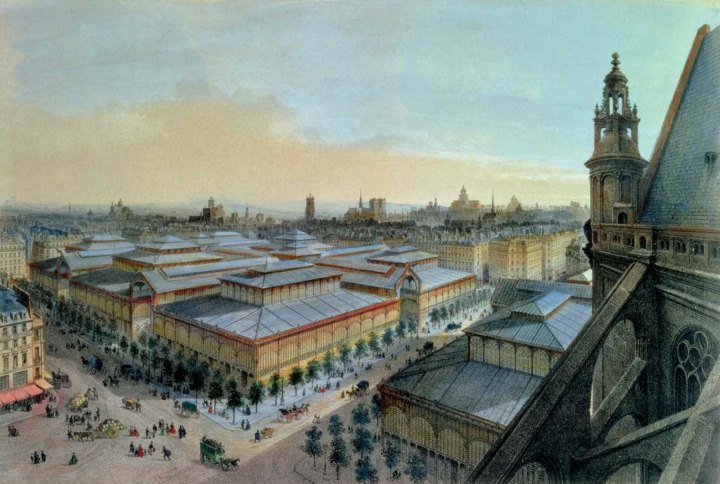

View of Les Halles in Paris taken from Saint Eustache upper gallery, c. 1870-80 (colour litho) by Benoist, Felix (1813-1896); Private Collection, out of copyright

View of Les Halles in Paris taken from Saint Eustache upper gallery, c. 1870-80 (colour litho) by Benoist, Felix (1813-1896); Private Collection, out of copyright

interior of dome

interior of dome

Les Halles has been called the “belly” of Paris, a name owed to Emile Zola’s novel Le Ventre de Paris (The Belly of Paris), published in 1873, three years after the opening of Les Halles. It should be no surprise that the novel contains descriptions of the market’s offerings. Descriptions that are some of the lushest I’ve read and probably in greater profusion than in any other book. For those who love food, it’s a joy to read.

Les Halles has been called the “belly” of Paris, a name owed to Emile Zola’s novel Le Ventre de Paris (The Belly of Paris), published in 1873, three years after the opening of Les Halles. It should be no surprise that the novel contains descriptions of the market’s offerings. Descriptions that are some of the lushest I’ve read and probably in greater profusion than in any other book. For those who love food, it’s a joy to read.

But the book isn’t just about the bounty (or glut) of the products the market yields. It’s, in fact, just one in a series of twenty books—maybe the largest of all time—chronicling the lives of the Rougon-Macqquart family. According to Brian Nelson’s Introduction to The Belly of Paris (Oxford World’s Classics). Zola intended the series to

“illustrate the influence of heredity and environment on a wide range of characters and milieus.”

Sounds like a psychological study (here’s another of another Victorian character)? Sure does, but in the form of fiction. The cycle or series places various members of this particular family at the core of each of the twenty books. In The Belly of Paris, that Rougon-Macquart is Lisa, the plump and beautiful, rosy, self-assured woman married to Quenu, the owner of a successful charcuterie. While her relatively simple-minded fat husband labors in the kitchen to make the products for the store, La Belle Madame reigns behind the counter.

The book, is so much more complex than it may appear on the surface and, like any great piece of art, each reader can potentially see in it something that’s unique to her particular perception. For me, one character that stood out is the young artist Claude, Lisa’s nephew, who returns as the main character in a subsequent book, L’Œuvre (The Masterpiece). He wanders around the markets in early mornings, admires the luscious colors of the produce and imagines painting them.

Claude may have been modeled after post-Impressionist Paul Cezanne, Zola’s friend from their childhood in Aix-en-Provence. Besides being a painter, Claude is something of a philosopher—a mouthpiece for Zola—as he theorizes about fat people swallowing up the thin ones. This clash of Fat vs. Thin is, in fact, a major theme throughout the whole book.

While the Fat prevails in Les Halles, some thin people do live around there. Aside from Claude, there is Florent, the unlikely hero. He brought up his younger half-brother, the fat charcutier Quenu who is devoted to him. Having escaped his exile in the prison of Cayenne (Devil’s Island) where he suffered constant deprivation of food, company, and sensory stimulation, you might think Florent would fatten himself up and thrive in Les Halles. But the abundance of food doesn’t make him salivate. It makes him want to puke. He’s a conscience-ridden ascetic who spends his hours thinking and writing about how to change things for the better. He threatens the status quo and the things that Lisa values. She becomes his silent, but powerful, enemy. In the end, Zola describes her:

She was a picture of absolute quietude, of perfect bliss, not only untroubled but lifeless, as she bathed in the warm air. She seemed, in her tightly stretched bodice, to be still digesting the happiness of the day before; her plump hands, lost in the folds of her apron, were not even outstretched to grasp the happiness of the day, for it was sure to fall into them. And the shop window beside her seemed to display the same bliss. It too had recovered; the stuffed tongues lay red and healthy, the hams were once more showing their handsome yellow faces,

The Belly of Paris is just as much about the characters—as richly-drawn as the produce—that inhabit Les Halles as it is about its life-giving (for the fat) but also nauseating (for the thin) bounty.

For a long time, French cuisine has been celebrated all over the world for its superior quality and craftsmanship. Every chef worth her salt wanted to master French culinary techniques. French gastronomy has been such an institution that UNESCO declared it an intangible cultural heritage in 2010, citing it as a “social custom aimed at celebrating the most important moments in the lives of individuals and groups.” A ritual and festive event using know-how linked to traditional craftsmanship.

Les Halles, I think, is both at the root of and an embodiment of French gastronomy, one that Emile Zola immortalizes in this sumptuous, biting book.